A team of researchers from the University of Gothenburg has made an unprecedented discovery that shore crabs, a type of crustacean, experience pain. This breakthrough, which was achieved through brain-testing techniques akin to EEG measurements, provides compelling evidence that crustaceans do indeed have neural responses to painful stimuli.

This research is part of a larger effort to improve the welfare of creatures that humans often consume as food. The focus is on decapod crustaceans, a category that includes popular seafood such as prawns, lobsters, crabs, and crayfish. Despite their widespread consumption, these shellfish are not currently protected under EU animal welfare legislation. However, this new evidence could potentially trigger a change in such regulations.

“The necessity of finding less distressing methods of killing shellfish is now more evident than ever, given that we have scientific proof of their ability to perceive and react to pain,” says Lynne Sneddon, a zoophysiologist at the University of Gothenburg.

Prior to this breakthrough, several studies had been conducted on crustaceans which involved exposing them to physical impacts, electric shocks, or acidic substances. The creatures’ reactions to these harmful stimuli led scientists to presume they were capable of feeling pain.

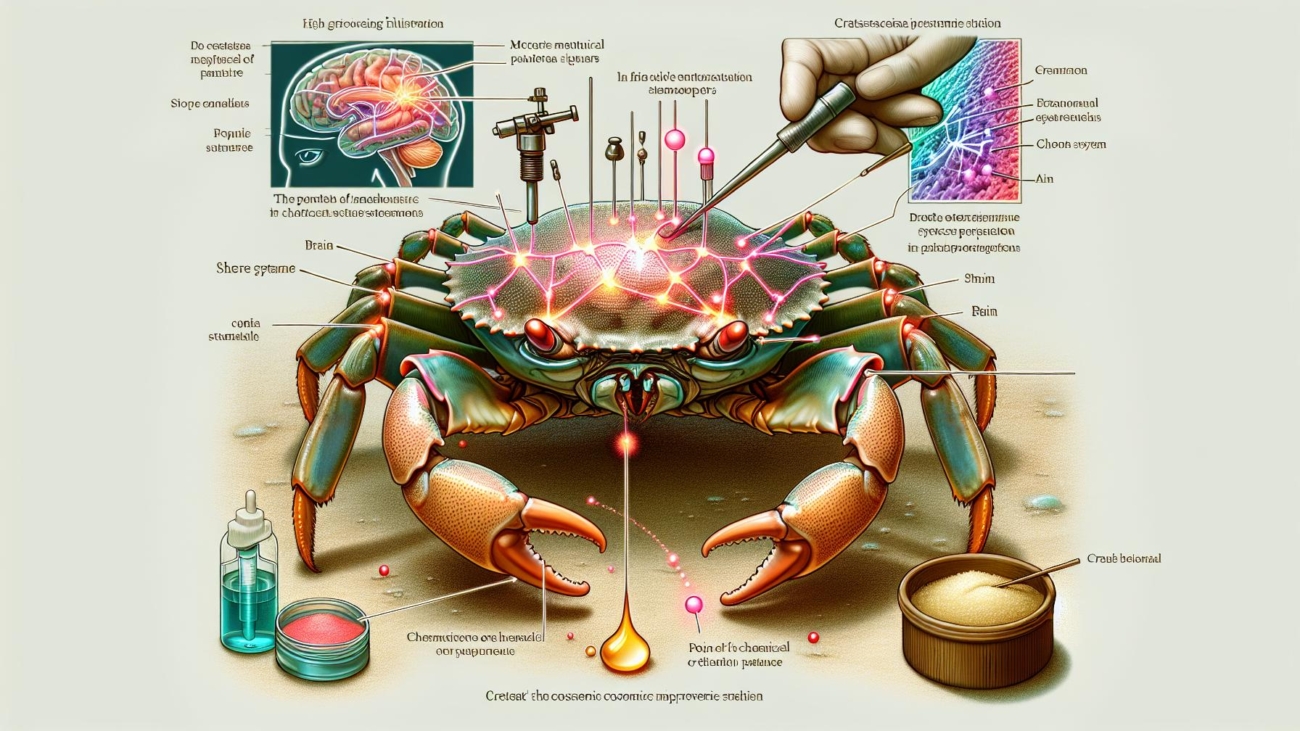

The University of Gothenburg research team is the first to substantiate this presumption through neurobiological studies. They conducted tests to measure brain activity in shore crabs and found evidence of pain receptors in the crabs’ soft tissues.

“When we exposed the crab’s soft tissues to a potentially painful chemical, or applied pressure to various parts of its body, we observed a spike in brain activity,” says Eleftherios Kasiouras, a PhD student at the university and the lead author of the study.

The researchers conducted these tests on the crab’s claws, antennae, and legs, and their findings indicate that these creatures possess a mechanism for transmitting pain signals from these body parts to the brain. Interestingly, physical stress induced a shorter but more intense pain response, while a chemical stressor resulted in a more prolonged reaction.

“It’s reasonable to assume that all animals require some form of pain system to help them avoid potential danger. Considering the similarities in structure and nervous systems among crustacean species, it’s plausible that shrimps, crayfish, and lobsters also have the capability to process pain,” Kasiouras adds.

The findings underscore the need for more humane methods of handling and even euthanizing crustaceans. Currently, it is permissible to dissect a crustacean while it’s still alive, a practice unthinkable for mammals we consume.

“Further research is required to discover less painful ways of killing shellfish,” reiterates Lynne Sneddon.