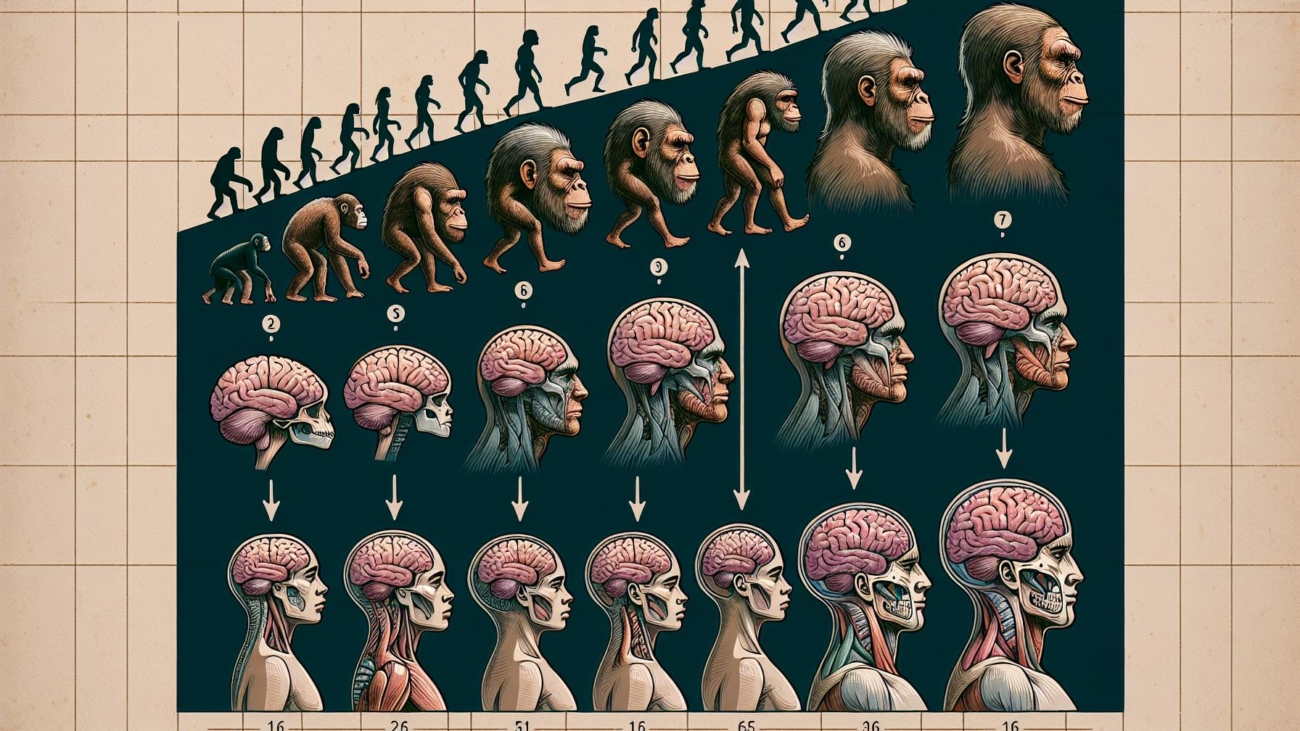

The evolution of the human brain has long fascinated scientists, and a recent study has unveiled a new perspective on this subject. Contrary to previous beliefs, the study suggests that the brains of modern humans and our closest relatives, including Neanderthals, expanded steadily over time within each species, rather than experiencing sudden growth spurts between different species.

This groundbreaking research, published in the journal PNAS, is the result of a collaborative effort by scientists from the University of Reading, the University of Oxford and Durham University. The researchers compiled the most extensive database of ancient human fossils ever, spanning a period of 7 million years. They paired this vast collection with advanced computational techniques and statistical methods to fill in gaps in the fossil record, providing an unprecedented view of human brain evolution over time.

“This study fundamentally alters our understanding of how human brains evolved,” said study co-author Professor Chris Venditti from the University of Reading. “Previously, we thought of brain evolution as a series of dramatic leaps, akin to upgrading from one model of a computer to another. However, our research suggests the process is more like a series of steady, incremental software updates within each species across millions of years.”

This research challenges the long-held belief that some species, like Neanderthals, remained fixed and failed to adapt. Instead, it emphasizes that gradual and consistent changes were the primary drivers of brain size evolution.

“Major evolutionary shifts don’t necessarily require dramatic catalysts,” said lead author Dr. Thomas Puschel, now at Oxford University. “They can occur through small, progressive adaptations over time, much like how we learn and adapt in the present.”

The study also discovered an intriguing pattern: while species with larger bodies generally had bigger brains, within a single species, brain size did not consistently correlate with body size. This suggests that the factors influencing brain size evolution over millions of years differ from those affecting brain size within individual species, adding a new layer of complexity to our understanding of how evolutionary pressures shape brain size.

Co-author Dr. Joanna Baker from the University of Reading added, “Understanding why and how humans evolved larger brains is a key question in the study of human evolution. Our research, studying brain and body size across many species over millions of years, reveals that our characteristically large brains resulted primarily from gradual changes within individual species.”

This enlightening study was funded by a £1 million Research Leadership Awards grant from the Leverhulme Trust, with the aim of deepening our understanding of human ancestor evolution.