October 29, 2013

There is no current evidence to prove that blood type diets will provide beneficial health effects, despite their prevalence within the diet and health industry, according to a recent review performed by the Centre for Evidence-Based Practice, Belgian Red Cross-Flanders and published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. In this systematic review, researchers screened 1415 references to the diet and after narrowing down the field to one potentially eligible study, concluded that no studies showed the health effects of ABO blood type diets.

“‘Evidence’ and ‘evidence-based’ are terms which are being used incorrectly in the industry, and potentially irresponsibly. This type of information is confusing to the general populace. Despite the fact that no evidence existed to support the health claims attributed to blood type diets, the diets were endorsed for more than a decade with millions of books being sold around the world. The proffered ‘evidence’ relied on studies, which did not assess the diets themselves, thus the claimed health benefits of the diets were, in fact, theoretical. What is particularly concerning is that during this extended period of time, nothing has been done to address this issue,” says Dr. Emmy De Buck, Manager Centre for Evidence-Based Practice (CEBaP), Belgian Red Cross – Flanders.

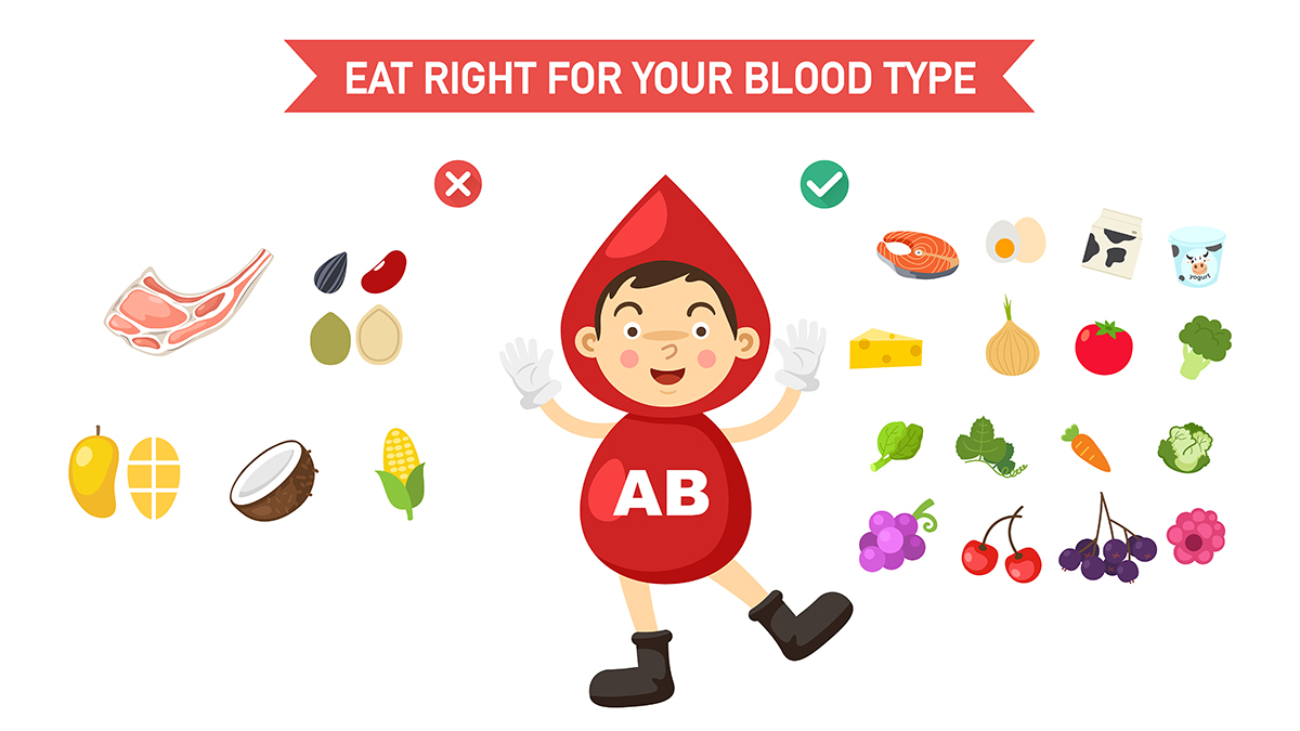

ABO blood type diets revolve around the idea that a person’s blood diet can provide a unique roadmap to dietary, exercise and medical treatment plans. In one of the most popular versions of this diet, introduced in 1996 by Dr. Peter D’Adamo in his book Eat Right 4 Your Type, type A’s should be vegetarians, type O’s should eat animal proteins and avoid dairy, type B’s should eat game and low-fat dairy, and type AB’s should follow some sort of combination of A and B recommendations. There are more than 7 million copies of this book in print in over 60 languages.

After narrowing down the potential studies to 16 that met some of the necessary criteria, only one warranted further investigation. This identified studied had looked at 254 subjects, grouped according to blood type. Intervention groups were given the objective of a 25% reduction in dietary fat intake, while control groups didn’t change their diets. LDL cholesterol values of both groups were measured over the course of 6, 12 and 18 months.

Researchers did find an association between blood groups and the variability of responses to a low-fat diet. However, this study was eventually eliminated because of study limitations and the indirectness of its association with the topic in question – namely, when grouped according to ABO blood types, do certain diets improve the health and/or decrease the risk of disease? And researchers here found no evidence of this.

It’s difficult to validate the health benefits of a diet, says De Buck, because first of all, health effects of a diet cannot always be measured immediately (a long term study is necessary), and secondly, because of a lot of other variables (known as “confounding factors”) can play a role in the relationship between the diet and (positive) health outcomes. For example, somebody who is following a diet might also be more health conscious, do more sports, and so on. Moreover, the effect of a diet can be different depending on people’s BMI, gender and other factors.

“An ideal study would randomly divide a group of people into an intervention group (following the blood type diet) and a control group (following a standard diet), in order to obtain similar distributions of virtually all possible confounding factors. Health effects should then be measured at regular time intervals during a longer period of time,” says De Buck.

It’s difficult to adhere to any diet over the long term, and most health professionals would caution against throwing all your weight – so to speak – behind any one of the many popular diets out there – especially without clear scientific research to support results.

While there is growing evidence that certain blood types may have an increased vulnerability when it comes to particular diseases, researchers in this study warn that when it comes to eating for blood type, consumers should be aware that the health claims surrounding these diets are thus far theoretical, and simply not proven by science.

“The actual concept of ‘evidence’ has not been properly disseminated to the broader population and therefore, those who make claims of ‘evidence’ need to be more responsible with their claims so that consumers are given the correct information upon which to base their own decisions. Until appropriate studies have been performed which assess the health effects of adherence to blood type diets, the health effects cannot be determined,” adds De Buck.